“Conspiratorial play is a universal of power politics, and where there is no limit to power, there is no limit to conspiracy”

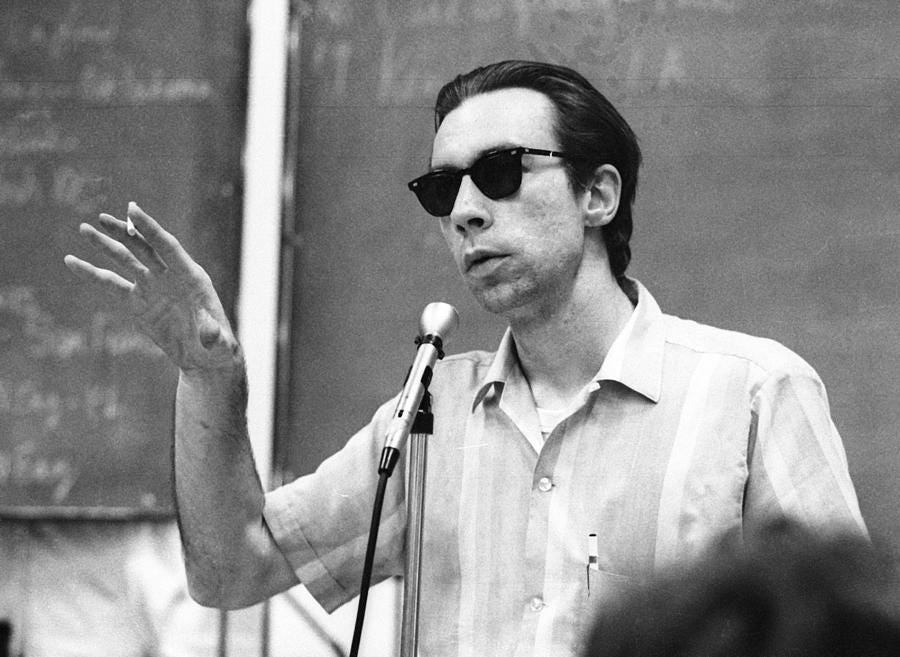

Carl Oglesby wrote The Yankee and Cowboy War in 1976 in the wake of Watergate and the establishment of the House Select Committee on Assassinations to reinvestigate the Kennedy and King Assassinations. Public concern over intelligence operations, both foreign and domestic, had never been higher. Dubbed ‘the year of intelligence,’ 1975 opened with the creation of the Church Committee, the first and most significant time congress has tried to exercise its constitutional authority for oversight of intelligence agencies. The committee led to revelations about mind control and psychological warfare in project MKULTRA, domestic propaganda through Operation Mockingbird, and domestic spying and counterintelligence through the FBI’s COINTELPRO and the CIA’s CHAOS. In the final chapter of the book, Oglesby expresses his hope that these committees will finally see the public state exercising control over the many tentacles of its clandestine apparatus. He asks us:

Will the new knowledge lead us only to accept the new state of total surveillance and to make new personal deals with the corruption and fascism implicit in its formations? Or will we turn the other way?

The Church Committee and HSCA did lead to new congressional oversight over intelligence including the creation of a permanent Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. And yet, it’s hard to imagine Oglesby would be happy with the answer to the question he posed almost 50 years ago. Did we turn the other way? Speaking at Georgetown in 2002, chief of Saudi Intelligence Prince Turki bin Faisal commented on the intelligence community's response to congressional oversight.

In 1976, after the Watergate matters took place here, your intelligence community was literally tied up by Congress. It could not do anything. It could not send spies, it could not write reports, and it could not pay money. In order to compensate for that, a group of countries got together in the hope of fighting Communism and established what was called the Safari Club. The Safari Club included France, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Morocco and Iran. The principal aim of this club was that we would share information with each other and help each other in countering Soviet influence worldwide, and especially in Africa.

The full story of the Safari Club is beyond the scope of this piece, but it would go on to play a central role in the principal intelligence scandal of the following decade, the Iran-Contra Affair. The way the international anti-communist intelligence networks seamlessly reorganized to bypass congressional oversight in the 1970’s is an emphatic confirmation of Oglesby’s main thesis: that “conspiracy is the normal continuation of normal politics by normal means.”

If you lived through Trump and covid-19, the idea that “conspiracy is the normal continuation of normal politics by normal means” will seem to you either plainly self-evident or unspeakably dangerous. The very idea of conspiracy has become highly politicized, and yet conspiratorial explanations for the geopolitical happenings of our times are found not only in the depths of 4chan or the YouTube algorithm, but all over nightly cable news in the form of the Russiagate explanation of the 2016 election and Trump presidency. On the day I’m writing this, the Financial Times published a piece by a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute entitled “Psy-ops are a crucial weapon in the war against disinformation.” They praise the development of the new Swedish Psychological Defence Agency, which will expose and combat “disinformation aimed at weakening public confidence in its military forces or political leadership.” In short, the Swedish military has just opened a domestic propaganda agency and the Financial Times and American Enterprise Institute think every free democratic country ought to follow their lead. Carl Oglesby is turning in his grave.

A poll released in May found that 15% of Americans believe in some of the core tenets of QAnon, including that “the government, media, and financial worlds in the U.S. are controlled by a group of Satan-worshipping pedophiles who run a global child sex trafficking operation.” In October 2020, the American Enterprise Institute (there they are again) polled Americans on their belief in a wide range of ‘conspiracy theories’ including about election fraud in 2016 and the origins of covid-19, and found most Americans believe in at least one conspiracy theory.

Plenty has been written about the rise in conspiratorial thinking. In their recent book A Lot of People Are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy, Harvard and Dartmouth professors Nancy L. Rosenbaum and Russell Muirhead admit that ‘conspiracy’ is an unavoidable conclusion so long as power is exercised covertly, but contend there is a new phenomenon at hand:

Conspiracy theory has always been part of political life. So long as those who exercise power are secretive and self-serving—and so long as democratic citizens value vigilance and even a degree of mistrust—it always will be. Some theories are far-fetched, but sometimes the dots and patterns that support a conspiracy theory prove the charge.

What we’re seeing today is something different: conspiracy without the theory. Its proponents dispense with evidence and explanation. Their charges take the form of bare assertion: “The election is rigged!” Yet the accusation does not point to any evidence of fraud.

In The Yankee and Cowboy War Oglesby seeks not simply to defend a conspiratorial view on politics, but to provide a theoretical framework to understand why “conspiracy is the normal continuation of normal politics by normal means.” He agrees with Rosenbaum and Muirhead that conspiracy is the predictable consequence of the covert exercise of power, but he is brave enough (or some would say reckless enough) to follow the logic and conclude that to understand power in contemporary American politics we must theorize about its operation in the dark. As the subtitle of the book - Conspiracies from Dallas to Watergate and Beyond - alludes, the primary conspiracies Oglesby deals with are the JFK assassination and Watergate. He sees these two monumental events in American history as connected through a clandestine struggle for control between two factions of the American power elite, who he terms the Yankees and the Cowboys.

The Yankees are the traditional Eastern Establishment, embodied most notably in the Rockefeller brothers David and Nelson, their main financial interests in Chase Manhattan Bank, and their round-table policy coordinating bodies the Council on Foreign Relations and the Trilateral Commission. With economic interests primarily in finance and trade, the Yankees view the American project in continuity with European and particularly British imperialism. Often called Atlanticists or Rockefeller Republicans, the Yankees seek a multilateral rules based world order in which Western capital plays a privileged role in setting and enforcing the rules.

Professor Peter Dale Scott calls the Yankee-Cowboy dialectic the “Prussians vs. the Traders,” emphasizing the differences in material-economic base of each faction. Where the Yankees are primarily engaged in finance and trade and located in Eastern urban centers, the Cowboys hail from the Southwest and West Coast and are invested in the business of America’s westward frontier expansion, including mining and manufacturing, oil and gas, and most importantly aerospace and defense contracting. The Cowboys see the American project as a great rupture, rather than a continuation, of the European imperial project and embrace the image of the pioneering Western frontiersman as their guiding icon. Oglesby uses Howard Hughes as the Cowboy prototype, and examines Hughes’ battle through the early 1970’s to maintain control over his aerospace and manufacturing empire against Eastern financial interests seeking to take his companies public. Where the Yankees want a multinational rules based order the Cowboys seek unilateral American hegemony. Where the Yankees look East to Britain and Europe, the Cowboys look West to the Pacific frontier.

In Oglesby’s view the JFK assassination was a Cowboy coup and Watergate was a Yankee countercoup culminating in the election of Jimmy Carter. Ultimately, I think Oglesby’s analysis of these events falls short, and there has been substantial research in each case that’s been published since 1976 that gives much clearer pictures than what Oglesby had at the time. For example in The Devil’s Chessboard, David Talbot makes a strong case that arch Yankee Allen Dulles was in the loop about the plans to kill JFK and gave his approval. From 50 years on, it looks more likely that in each case a president was removed from office not because one faction or the other won a battle over the presidency, but because the defensive side finally agreed with their opposition that their President had to go.

Oglesby’s greatest success with The Yankee and Cowboy War is not in theorizing the conspiracy of JFK or Watergate, but in developing a theory of political conspiracy in general: what he calls “clandestinism.” It’s a framework in which the public history that we witness on the surface is caused by subliminal undercurrents in the struggles between factions of the power elite. Where the competition over the highest echelons of public office and public policy is carried out in private with cloaks and daggers.

Implicit in this view is the threat to democracy. Not from those who believe in conspiracy but from those with power who wield it in secret for personal ends. The final chapter, entitled “Who Killed JFK,” is not a theory of the case, but rather a plea for the politicization of the question. This feels a rather ineffectual policy prescription in light of the frightening threat to freedom presented by Oglesby’s analysis of concentrated covert power in the preceding pages, though there is still much to be learned from the analysis.

Yankee and Cowboy do not denote hard set factions or exclusive membership clubs, but heuristics for understanding differences among the power elite in their general view towards politics, foreign policy, or their economic interests. ‘Yankee vs. Cowboy’ emphasizes a difference in the historical role of the American project. A continuation of European domination, or an individualistic break with tradition for new forms of freedom. ‘Atlanticist vs. Neocon’ emphasizes a difference in foreign policy. A multipolar rules based order which looks to our European peers in the East, or a unipolar American Imperium which looks to the West and South at a developing world to be dominated. ‘Prussian vs. Trader’ emphasizes the differing economic bases. Eastern finance capital with its banking and trade cartels, versus Western independent industrialists with massive mineral and oil deposits and fat government contracts for airplanes and missiles.

It’s worth here excerpting a substantial quote to give the full context to what Oglesby means by his thesis that “conspiracy is the normal continuation of normal politics by normal means.” He is discussing the history of the Round Table Groups, which are policy coordinating groups staffed by members of the highest level of political and economic elites, and which have been written about by historian Carroll Quigley in his works The Anglo-American Establishment and Tragedy and Hope. Here Oglesby fully articulates his views of clandestinism and makes a strong defense of a conspiratorial view of history which does not reduce to an omnipotent cabal of power (emphasis added):

Am I borrowing on Quigley then to say with the far right that this one conspiracy rules the world? The arguments for a conspiracy theory are indeed often dismissed on the grounds that no one conspiracy could possibly control everything. But that is not what this theory sets out to show. Quigley is not saying that modern history is the invention of an esoteric cabal designing events omnipotently to suit its ends. The implicit claim, on the contrary, is that a multitude of conspiracies contend in the night. Clandestinism is not the usage of a handful of rogues, it is a formalized practice of an entire class in which a thousand hands spontaneously join. Conspiracy is the normal continuation of normal politics by normal means.

What we behold in the Round Table, functioning in the United States through its cover organization, the Council on Foreign Relations, is one focal point among many of one among many conspiracies. The whole thrust of the Yankee/Cowboy interpretation in fact is set dead against the omnipotent-cabal interpretation favored by Gary Allen and others of the John Birch Society, basically in the respect that it posits and [sic] divided social-historical American order, conflict-wracked and dialectical rather than serene and hierarchical, in which results constantly elude every faction’s intentions because all conspire against each and each against all.

This point arose in a seminar I was once in with a handful of businessmen and a former ambassador or two in 1970 at the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies. The question of conspiracy in government came up. I advanced the theory that government is intrinsically conspiratorial. Blank incredulous stares around the table. “Surely you don’t propose there is conspiracy at the top levels?” But only turn the tables and ask how much conspiring these men of the world do in the conduct of their own affairs, and the atmosphere changes altogether. Now they are all unbuttoned and full of stories this one telling how he got his competitor’s price list, that one how he found out whom to bribe, the other one how he gathered secret intelligence on his own top staff. Routinely, these businessmen all operated in some respects covertly, they all made sure to acquire and hold the power to do so, they saw nothing irregular in it, they saw it as part of the duty, a submerged part of the job description. Only with respect to the higher levels of power, around the national presidency, even though they saw their own corporate brothers skulking about there, were they unwilling to concede the prevalence of clandestine practice. Conspiratorial play is a universal of power politics, and where there is no limit to power, there is no limit to conspiracy.

Writing here about a “divided social-historical American order, conflict-wracked and dialectical,” Oglesby sounds like a trained Marxist. In the closing of the book he outlines his politics, centered on the “traditional values” of small ‘d’ democracy, small ‘r’ republicanism, and independence. Elsewhere, he’s described his own political orientation as “radical centrist” or “centrist libertarian,” all of which situates him well within an American liberal political tradition. Though as blogger LorenzoAE points out in his essay “Noam Chomsky and the Compatible Left,” Oglesby’s thinking takes on a decidedly Marxist view contra his liberal training.

Despite Oglesby’s self-identification, his place in the struggle caused him to develop the sort of organically materialist thinking that comes from marrying objective study to revolutionary action. In the pages of his seminal 1976 book The Yankee and Cowboy War, which remains one of the best books on America’s ruling classes, he ended up sounding like a Communist: “The distinction between the East Coast monopolist and the Western tycoon entrepreneur is the main class-economic distinction set out by the Yankee/Cowboy perspective. It arises because one naturally looks for a class-economic basis for this apparent conflict at the summit of American power. That is because one must assume that parties without a class-economic base could not endure struggle at that height.”

“Clandestinism is the formalized practice of an entire class in which a thousand hands spontaneously join”

Without knowing it Oglesby has hit on a core structural element of capitalism which Marx outlined in his critique of political economy. As members of the ownership class, capitalists are constantly engaged in two forms of class struggle, and they need to win these struggles to maintain their existence as capitalists. These two forms are intra-class struggle against other capitalists through competition over market share, resources, and productive capacity, and inter-class struggle against the working class from whom they seek to purchase labor for the lowest possible price. The Yankee/Cowboy divide highlights a particular aspect of intra-class struggle between factions of capitalists.

The interests of specific individual capitalists are often at odds with each other due to market competition, but they are aligned vis-a-vis the working class in that every capitalist wants to maintain favorable negotiating positions with labor. The Cold War transformed the inter-class conflict between workers and capitalists, usually occurring within the workplace or industrial sector, into a geopolitical issue with center stage on the Grand Chessboard. This is why the Yankee/Cowboy conflict explodes so violently in the Dallas to Watergate decade. The development of the international communist “conspiracy” means that differences over foreign policy are no longer mere political differences but differences of strategy in an existential war for capitalism. It’s the transmutation of class conflict into geopolitical conflict which raises the stakes high enough that both the Yankees and the Cowboys decide they need to commit fratricide when Kennedy starts trusting Kruschev and Castro more than he does his own Joint Chiefs of Staff.

An old Indian parable tells of a group of blind men who encounter an elephant for the first time. To get a sense of this unknown creature they each begin to touch different parts of the elephant; one the trunk, one the tail, one the leg. “This beast is long and muscled like a snake,” one said. “No, it is broad and tall like a tree trunk,” claimed another. Making sense of political conspiracy is a lot like trying to grasp an elephant as a blind man. The ground truth of reality - the truth of the conspiracy - is fundamentally hidden from you, and you can only get a semblance of it by combining every piece of information you have and being flexible about different interpretations. In some tellings the men come to blows over their disagreements about how to interpret the elephant. The lesson here being that there can be dire social and political consequences to interpreting reality too rigidly based on subjective and partial information.

One lesson from studying Watergate is that what counts as conspiracy theory or official narrative is a political question. Everyone has a conspiracy theory about Watergate. The entire saga is a conspiracy. A conspiracy to conduct political espionage was caught, and the president was impeached over a conspiracy to cover it up. Nixon wanted to cover up Watergate with a conspiracy theory laying it all at the feet of the CIA. After all, three of the burglars were career CIA officers in James McCord, E. Howard Hunt, and Frank Sturgis. Publicly blaming the CIA would weaken Nixon’s political rivals while also centralizing more power for state surveillance in the Whitehouse. But McCord wouldn’t go along with it and blew the whistle. Oglesby posits McCord was a Yankee plant put into Nixon’s inner circle by CIA director and Yankee Richard Helms and that McCord’s true loyalty was to the CIA.

Len Colodny and Robert Gettlin have another conspiracy theory in their 1992 book Silent Coup. In their telling, the prime conspirators are the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who are upset at Nixon for being sidelined on foreign policy decisions, particularly with his pursuit of detente with China and the USSR. They saw the Yankee National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger taking the lead on foreign policy and softening Nixon’s hardened anti-communism as unacceptable. This is interestingly almost the exact opposite thesis of Oglesby on Watergate. Colodny and Gettlin see a Cowboy conspiracy centered on the JCS who are upset because the anti-communist Cowboy Nixon is getting too close to Yankee Kissinger and weakening his stance on the reds. As Oglesby alludes to in the passage excerpted above, the ultra-right Cowboy John Birch Society spread the conspiracy theory that international communism was controlled by the Yankees through the Rockefeller and Rothschild families. An American bastardization of the antisemitic judeo-bolshevik conspiracy. It seems some of the Cowboy grand strategists may have taken this propaganda to heart.

Ultimately each of these stories have some of the truth in them. McCord was a Yankee plant, and as Oglesby and many journalists since have pointed out, many of his actions during the burglary indicate he wanted the burglars to get caught. The JCS were pissed at Nixon over detente with China, but more importantly so was the entirety of the Cowboy overworld including groups like the John Birch Society, the Committee on the Present Danger, and the American Security Council. They may have had different reasons, but the Yankees and the Cowboys were united in wanting Nixon gone at the time of Watergate. And yet, if this is anything resembling the capital T Truth of Watergate, we could only get there by acting like blind men discovering an elephant, combining knowledge from many sources.

On January 24th, 1967, the CIA dispatched memo 1035-960 to station chiefs, entitled “Countering criticism of the Warren Report.” It opens noting a recent poll which showed some 46% of Americans did not think Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone in assassinating JFK or had questions about the integrity of the Warren Commission report. “The trend of opinion is a matter of concern for the U.S. government including our organization,” the memo reads. It goes on to outline a plan for combating this recent shift in opinion, which includes emphasizing the conspiratorial nature of the critics views, and instructing CIA station chiefs:

To employ propaganda assets to answer and refute the attacks of the critics. Book reviews and feature articles are particularly appropriate for this purpose. The unclassified attachments to this guidance should provide useful background material for passage to assets.

The memo also offers six talking points that their propaganda assets defending the Warren Commission can engage in, including that “conspiracy on the large scale often suggested would be impossible to conceal in the United States, esp. since informants could expect large royalties.” This view that ‘someone would have talked’ is a common trope among anti-conspiracy talking points, but it’s interesting to see the CIA issue this point to their media assets in the JFK case, because many people did talk. There have been thousands of pages written about people revealing prior knowledge of the JFK plot. The story Oglesby tells of one witness, Rose Cherami, is typifying of the effect political conspiracies, and their continued coverup, have had on the American public.

At the time of the assassination Cherami was working as a stripper in one of Jack Ruby’s clubs. Two days before the killing she was driving through Louisiana with two men on a trip to pick up heroin from New Orleans on behalf of Ruby. An argument ensued and the two men beat her bloody and threw her out of the moving car on a state highway in Louisiana. She was found by police and immediately told them she had information about a plot to kill the president. They thought her a hysterical junky and when she went into heroin withdrawal she was transferred to Jackson State Mental Hospital. Multiple nurses at the hospital report that on the morning of November 22nd, 1963 they were watching television of Kennedy’s trip to Dallas and Cherami stated “this is when it is going to happen” immediately before Kennedy got shot. In the days after the assassination, but before Ruby killed Oswald, Cherami told the chief psychiatrist at Jackson State, Dr. Victor J. Weiss, that she knew both Ruby and Oswald and had seen them sitting together at Ruby’s club.

Cherami says that the argument in the car started because she heard the two men talking about the plot to kill Kennedy and she asked them what they were talking about. There’s a bit of Rose Cherami in every American. A life of heroin addiction and sexual predation culminating in being beaten bloody, gaslit, and sent to a mental hospital for daring to ask about the truth. In 1965 Cherami was hit by a car and killed, although some evidence suggests she was shot in the head beforehand. Some JFK conspiracy theorists have insisted this confirms her story, but as CIA memo 1035-960 reminds us, “such vague accusations as that ‘more than ten people have died mysteriously’ can always be explained in some more natural way,” so there’s obviously nothing to worry about there. Cherami’s story is almost completely lost to history, for as we know, history is written by the victors. And in class war, both the Yankees and the Cowboys can win, so long as the proletariat loses.

Stellar article

This is by far one of the best, most well written & well researched substack articles I have read in recent years.

Where is part two?